This is the method I use since many years. I feed my scrapings with half the water and half the flour that I need for a bread (ex. 100g needed = 50g water+ 50g flour) at 9h in the evening and let it at room temperature. Next morning, starter has doubled, so I take the quantity needed and put it back to fridge until the next time. This way I always have the quantity I need and never have to throw out discard.

@wendyk320 It’s good to hear this approach works well with longer stretches between baking. Actually I could see that it might be beneficial to the overall health of the starter (more ripening cycles) for the starter and the levain be one and the same especially if someone bakes less often.

@bakerodeo My favorites are the pancakes, crackers and naan recipes I linked to in the beginning of the recipe. Also these sourdough buckwheat crepes are easy and tasty with a little jam.

@ericjs Good point – I’ll have to measure some starter at my next bake ![]()

![]()

![]()

@ddrezner Yes!! So excited about Desem. Breadtopia is going to have blog posts about making the starter and baking with it soon. I’ll attach a pic preview ![]()

@markzec wow, I didn’t realize starter could do so well in the freezer. Thanks for sharing your starter method.

@oaklandpat Whole grain flours, especially rye whole grain flour, are going to make starter mature a little faster. That’s offset a little by the dryer consistency of the starter with whole grain if you’re sticking to 100% hydration – but yes, a little shorter time to ripen.

@mjodoin Nice! That sounds like an efficient and nicely predictable starter schedule.

Thank you so much for posting this and for all the comments and suggestions!! As a very new to sourdough baker, this is all very helpful and makes the starter maintenance a little less overwhelming!! Happy baking everyone!!

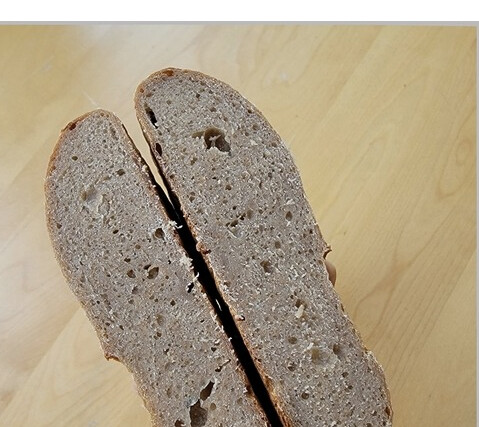

I hope that you do a side-by-side comparison with a more typical 1:1 starter with equivalent extraction. There was a lot of hype around desem some time back, touting it as the best whole wheat bread ever, different from a “standard” sourdough wheat. I’ve tried it, and I didn’t really notice much of a flavor difference, but of course there are so many variables that maybe something about my conditions / techniques either gave me substandard desem or produced comparable results with the 1:1 starter. So I’d love to see another take on that with your usual rigor!

I need to repeat the experiment, but my first attempt at this test yielded the same impression/result you had. The starters definitely smell different, and the doughs smelled different during fermentation, but I couldn’t discern a difference in flavor in the two loaves when baked. My husband actually thought I was tricking him by claiming the slices he tasted came from different loaves.

When incorporated in dough about 1/3 of baker’s yeast dies in the freezer. Add 50% more yeast to a recipe for frozen dough to account for the loss. Don’t know if wild-ish yeast has the same mortality rate, but suspect it isn’t much different. Might be worth a side-by-side bake using previously frozen starter and fresh starter.

When I froze a sourdough dough for two weeks (Experiment #1 in the post below), it seemed like there was a big die-off of microbes. The bread was disastrous and I was relatively patient (7 hours RT + overnight refrig).

I assume the concentration of microbes in a bulk fermented dough is smaller than in a ripe starter, and that’s why frozen starter can hand in there.

Plus, you’d take that frozen starter, defrost, feed and give it TLC. Whereas I defrosted the dough 24 hours in the rerfrigerator, shaped it, and waited for magic that didn’t happen lol.

![]()

Maybe the end result will just be a myth busted!

What temperature were you able to store it at? I remember getting the impression that typical refrigerator temperature was a little colder than was ideal for desem. I used a small bar fridge where the temperature at the bottom front seemed to stay around 50F. I also remember having doubts whether that was close enough either…maybe it was supposed to be somewhat higher.

I created the starter over two weeks at 55F in a temp controlled cooler, dry ball buried in flour, feedings every 2-3 days (center of dry ball extracted and used for new ball).

Now it is stored in my refrigerator in a jar, at a slightly higher hydration, and still with flour on top.

I read this article and I am made of questions. I never measured my starter before feeding it and it’s been a guessing game. How many times do I have to feed my starter with 1:1:1 before it consistently doubles in volume like the photo shows?

I read where you put your loaves in the fridge after the first rise to delay the baking start. How? After my first rise I put into bannetons and hope for the best.

Finally, is it possible to have firm loaves for decorating with a lame and still have holes in the bread after baking? My loaves aren’t firm enough but do rise in my Dutch ovens while baking. Sometimes.

Thank you!

I didn’t weigh my feedings before becoming a recipe developer and a sourdough educator, so take all of the precision with a grain of salt. You simply want to feed the starter with more flour and water than existing starter, in most situations.

It will probably take just one feeding for your starter to double after a 1:1:1 feed. The key is to not leave the starter sitting out at room temperature for a long time after it has consumed all the food – in my practice, this is no more than a couple of hours after it has started deflating, and preferably it is going into the refrigerator a little before peak so it has food while in there. Warm starvation will weaken the starter and could even make it proteolytic. You can read this forum thread to learn more about that.

And here’s even more reading that should answer the above question more thoroughly as well as explain refrigerating dough during the final proof, developing strong dough, whether wet or dry, and scoring.

Hi Melissa,

Interesting article, as always, on a basic point.

Personally, I use a different ratio, as discussed in the following video:

That is, rather than 1:1:1, something more like 0.02:1:1 – I just use the scrapings in the jar, as shown below. Once I’ve added the flour and water, I immediately stick the jar in the refrigerator. The total amount of sourdough depends on how much I plan to use next time. Generally I culture half of what will be needed, and get the other half by feeding it up the day I use it, 1:1:1, but it works fine to make the full amount and use it out of the jar. There’s probably a difference in elasticity, but as a practical matter I’ve never noticed anything.

I used to do this, a bit more high maintenance:

I’ve been doing it this way for at least a year, and wondered how the culture was standing up – whether keeping it in the refrigerator that way was selecting for bacteria that were best adapted to cold, for example. Recently I got some new starter and baked a couple of loaves to compare, and didn’t notice any difference due to which starter was used, either in rising time or taste. It would be good to know if other people get the same results.

This reminds me of when I was in a high school summer school and interned at a civil engineering lab. They were working on treating paper mill wastes before they were released into rivers, and the idea was to have microorganisms predigest it. The study was intended to determine the optimal conditions for the bacteria to feed and grow, in terms of pH and micronutrients. That was evaluated partly in terms of biological and chemical oxygen demand – that is, how much oxygen the predigested waste would use up when it got to the river. In the case of sourdough, you’d probably want to just put some under a microscope and see what populations of bacteria you get.

It would be interesting to know what was going on in sourdoughs, anyway, and I’m sure somebody must have looked at that. In general, the old Pasteur model – isolate a species and feed it up to get lots of cells to study – turns out not to be very realistic. In the wild, bacteria are typically starving, to begin with. But more to the point, they’re typically found in consortia, which is to say, they form units consisting of a number of different species in cooperation. The members of a consortium complement each other – the waste products of one might be useful to others, for example; in effect, it’s a small ecosystem. We’re very much like highly advanced consortia ourselves, as multicellular organisms.

My guess is that sourdough cultures work as consortia, and that it would be difficult to drop out one or more species without compromising the consortium as a whole. That is, I’d think that it would be obvious if constraining a sourdough culture to feed and reproduce in cold conditions exerted a lot of selective pressure. But that’s just a guess.

I’ve wondered the same thing about my starter because it also spends most of its life in the cold. The consortia idea makes sense. (Back when I wrote for a cystic fibrosis non-profit, I learned about how different bacteria and viruses cooperate or crowd each other out in the lungs.)

I did an experiment a while back comparing a from scratch rye starter with my existing starter converted to rye flour, and the two sustained different smell, appearance, and bread-flavor production for somewhere between 9.5 and 12 weeks. By 12 weeks the starters had 30 feeds. I kept up the experiment until 19 weeks (40 feeds).

What caused the flavor shift of the from scratch starter could have been the maturation/settling of the consortia or something else. Here’s that experiment if you want to check it out. Someday I should repeat it and change up some of the variables.

The methods of developing starter for panettone baking seem to indicate the consortia can be manipulated with changes in starter hydration, temperature, washing the starter, binding it etc. That is talked about here:

Also making a sweet stiff starter with the addition to sugar to the starter build. The second paragraph of this forum comment discusses that:

The scrapings method you do sounds a lot like that of Baked by Jack (YouTube) – he also refrigerates the scrapings. I do one feed of the scrapings before refrigerating, half out of habit and half so I have enough starter to bake a few days later with the starter directly from the refrigerator. If my bake days were more spread out, I think refrigerating scrapings would make more sense. Though a tiny bit of old cold starter works great too if you have the patience.

You and I are doing something similar, and unlike what Jack does. Where you’re careful to do 1:1:1, I don’t tie the amount I feed the scrapings to their weight – I just add flour and water according to the amount of starter I’m going to need later on. If it takes longer for the starter to ripen that way, that’s actually an advantage, since I won’t be using it for a week or so. In the same spirit, I don’t let the fed culture ripen before I refrigerate it.

Otherwise, I might use the starter straight out of the jar, but more often I just make half the starter I’m going to need, and double it on the day I use it. Thus this time it’s a full 1:1:1 feeding, not a snack. Obviously there are a lot of ways to do this…

On a similar note, I’ve wondered about this: is it useful to either let a sourdough-based dough rise for some amount of time before refrigerating it, or let it warm up and rise a little before shaping it? I’ve played around with that a little, since I don’t think the dough rises fully if it goes straight into the fridge, and haven’t come to many conclusions. I’ve drifted into letting it rise for an hour or so before I refrigerate it, but I don’t actually know whether it’s helpful.

Nice experiments! The questions you look into are always interesting, and it’s a relief that they’re actually being tested, rather than left to folk belief.

As an example of how fallible traditional methods can be, the dogma about cooking pasta has been that you need 4-6 quarts of water and have to keep the water boiling. In fact, you need much less water – for one serving, I use a quart or less. More interestingly, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist named Giorgio Parisi has found that you don’t need to keep the water boiling, either. You can bring it to a boil, add the pasta, bring it back to a boil (or not), cover it, and turn off the heat. Needless to say, there’s been a lot of kickback. In my experience, though, this works perfectly, at least on an electric stove, and, even using a small amount of water, the pasta cooks in exactly the same time.

Ah I get it now.

I’m all over the map as to when I refrigerate lean doughs, and I’ve found that bread quality is fine regardless – as long as you’re watching the expansion of the dough. I agree that when you refrigerate early, you’re tapping the brakes on the exponential population increase of microbes early on their curve upward, so the bulk fermentation can take a lot longer.

I would not recommend refrigerating enriched sourdough doughs unless the bulk is basically over, and even a final proof in the refrigerator can be paralyzing.

HA! I love that pasta data. Thanks for sharing. I get a lot of flack from my better half for crowding the pasta in a small amount of boiling water – but I stir to prevent sticking and my pasta comes out great – so why am I going to bring a huge vat of water up to a boil for 35 minutes if I don’t have to?

Yes, I tend to find that about a lot of sourdough baking. You go in thinking you’ll tweak this variable or that, and it rarely matters. That’s not surprising, since these microbes evolved under tough conditions. They’re out to take over their corner of the world no matter what.

The current subject is a case in point. I used to wonder if I should let the starter ripen before I refrigerated it. I also used to do something closer to 1:1:1. Did any of that affect the results? Not as far as I can tell. In fact, I’ve never kept track, but I don’t have the impression that it even changes the timing very much.

As for pasta, I’ve never had a problem with sticking. I stir it when I add it to the pot, the end, and anyway if you’ve turned the heat off, you don’t want to open the lid while it’s cooking. There’s a folk belief that adding oil helps prevent sticking, but in fact studies show that the oil doesn’t even come in contact with most of the pasta.

For whole grain pasta, at least, it seems to be a non-issue. And it isn’t an organic-at-all-costs sacrifice; the texture and taste of good whole wheat spaghetti is not qualitatively different from that of spaghetti made from refined flour.

You might be familiar with a British writer named Elizabeth David, and if you aren’t, you might want to get her French Provincial Cooking, for example. She wrote a book on Italian cooking around 1950, and since this wasn’t mainstream for a post-war British audience, she felt she had to explain that you don’t actually have to soak pasta overnight before you cook it. That sounds strange now, but it turns out that it really does cut the cooking time it you do. I’ve never tried it myself; the method described earlier – bringing the water to a boil, and then covering the pot and turning off the heat – reduces the energy use to the theoretical minimum, anyway.

This reminds me a little of how some people boil and drain their rice and others think that’s a crime ![]() In the end, there are a lot of effective ways to arrive at tasty food.

In the end, there are a lot of effective ways to arrive at tasty food.

I do find a texture difference in whole wheat pasta vs refined flour pasta, so my preference is to make it about 50:50 (AP : durum or khorasan whole grain flour).

Hi, I am brand new to breadtopia. My head is spinning. I don’t understand how much starter to use to make a load of bread. I didn’t realize you could mix the starter and use it almost immediately. Newbie!